Contents

by Monika Jaeggi

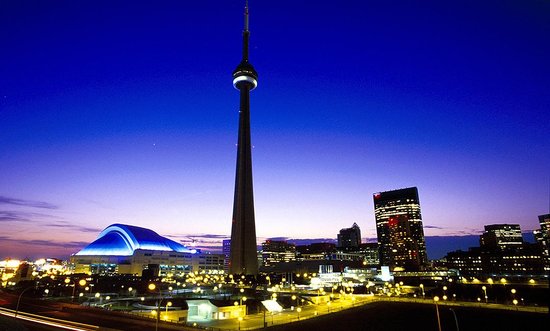

Known for years as one of the most narrow-minded and uncosmopolitan of the British colonial cities, Toronto has become the most culturally diverse city in the world since the 1960s as a result of rapid immigration. International surveys also identify Toronto as one of the most livable cities in the world, due in part to city planning initiatives and citizen activism of the last 20 years.

Toronto is divided into two distinct parts: the old downtown neighborhood areas in the City of Toronto and the modern suburban cities of North and East York, York, Etobicoke and Scarborough. The City of Toronto, also called the “city of neighborhoods”, has mostly straight streets and short blocks, with high-density housing, mixed-use development, and apartments built over small retail stores. A number of green spaces (parks and ravines) and good public transportation (buses and a subway) are among the amenities for residents.

The subdivisions in suburban areas are quite different. Streets are curved, development is much less intense, access to public transportation is often limited, and there is a clear distinction between shopping areas, workplaces and residential areas.

Downtown Toronto’s neighborhoods include Little Italy, Portugal Village, Little India, the Annex, Greek Village, Chinatown, Yorkville, Cabbagetown, and Seaton Village, to name a few. These areas are in much demand as shown by the constant demand in the real estate market. The Congress for the New Urbanism, recently held in Toronto, identified these communities as alternatives to the common North American suburban landscape — an urban village model that is neither city nor suburb but something in between.

Safe Public Spaces: Porches, Sidewalks, Parks

I live in Seaton Village which is located in the southwest of the city and was one of the areas of Italian settlement in the early 1950s, when the first post-war wave of immigrants from Southern Italy arrived in Toronto. Seaton Village is adjacent to Little Italy, the Portuguese neighborhood, and the Annex. It also has a little Koreatown within its boundaries.

What exactly is it that makes living in these neighborhoods attractive?

Most obvious for anyone strolling through is the fact that these are places for people, not for cars. No expressways cut through these areas. Streets are narrow (as little as 16 feet wide). They are usually one-way, and are often lined with century-old trees which are protected and cared for by the City of Toronto. Generous space is given to sidewalks, front yards, and parks rather than garages and parking lots. Garages are in the back of the houses along alleys which can be an adventure to walk through.

A variety of housing forms contribute to an interesting and diverse mix of economic classes and ethnic groups. The houses themselves all look different from one another. Sidewalk cafes, patios, restaurants, community theaters, public libraries, small retail stores (meat stores, fruit markets, bakeries, etc.), and public laundries on streets such as Bloor, College, Queen, and Dundas add to the diversity and public life of the neighborhoods. Corner stores are a particular landmark.

The small immigrant working-class houses are designed for social interaction. Porches accommodate families and neighbors who sit and chat at any time of the day. Activity reaches a peak in the evening, which is a particularly good time to stroll through the neighborhood and take in the different sights, sounds, smells, and tastes. At that time of the day the sound of foreign languages, including Portuguese, Italian, Spanish, and Chinese, is mixed with the smells of the predominately Mediterranean cuisine.

Among my favorite sights are the immigrant gardens. All sorts of herbs, vegetables such as tomatoes, beans, and zucchinis, and grapes and fruit trees grow in these fascinating places. Gardens are cultivated in both the back and front yards and tell a lot about the residents and their cultural roots. For example, every fall I see my neighbors from Southern Italy prepare winter cooking supplies in their back yard. The men cook fresh tomatoes in a big pan over an open fire while the women grill peppers and other vegetables and prepare them for storage in the basements. Wine making is also part of the fall garden activities as is the competition over the heaviest zucchini.

The sounds, smells and different languages disappear quite abruptly once one crosses Bathurst Street and walks east into the Annex. In this neighborhood close to the University of Toronto, many of the large Victorian houses are owned by faculty or rented to students. Colorful flower beds and old trees replace the vegetable gardens. However, here as well front yards offer ideal places to start conversations with people sitting on the huge porches. These yards are also places of business on any given weekend from spring to fall, when yard sales contribute to a lively atmosphere in the neighborhoods.

This interactive layout of houses, gardens, yards, and sidewalks — a pattern missing in the suburbs — creates an atmosphere of social control and security. These neighborhoods are especially safe for women since porches, sidewalks and parks are busy in various ways during the day and in the evening, sometimes until late at night.

The neighborhoods are active socially and politically. Streets are closed for traffic during street festivals and for a range of other social activities. Recently, the residents of Seaton Village were successful in preventing a Seattle-based coffee enterprise from taking over Dooney’s, a locally-run Italian restaurant and community institution on Bloor Street. The neighborhood association also successfully fought to reduce the size and improve the aesthetics of a recent superstore on the neighborhood’s fringe. The group developed a new street plan (new signals and planters on most streets) to reduce through-traffic created by the store, with implementation financed by the store. In addition, the city recently improved Bloor Street by widening sidewalks and providing more bicycle parking.

What about the downside of the Seaton Village and Annex neighborhoods? There is too much cut-through traffic. Rents are sky-high. There are too many dogs in the parks, and conflicts over cleaning up the dogs’ messes are ongoing. Also, ever since I moved here four years ago, Bloor Street, one of the main business streets in the area, has been in apparent economic decline, with the number of homeless people on the street increasing and shops closing one after another. Business owners say that rents are too high, and that they need to attract more customers from out of the area but there is not enough parking. However, new parking lots would probably attract a different clientele and lead to a more suburban atmosphere.

The Call for Neighborhoods — Toronto’s Planning History

As in the U.S., urban renewal schemes in the 1950s and 60s focused on rebuilding downtown Toronto as a new city. Plans called for hundreds of older working family houses to be expropriated, demolished and replaced with high-rise social housing. Although several of these schemes were actually carried out, other proposals for clearing old neighborhoods were stopped by citizens’ opposition.

Public outcry also focused on the expressways planned to link the city with growing suburbs. A ten-year fight by citizens against the planned extension of the Spadina Expressway was successful in 1971. This expressway would have cut right through the downtown neighborhoods, in particular the Annex.

Citizen opposition to the city’s modernization programs was particularly strong between 1965 and 1973. With the help of community organizers, low-income neighborhoods became successful at fighting new development. In 1972 the preservation forces won in the City of Toronto under the banner of “Preservation of Neighborhoods.” Neighborhood planning became a priority, and many activists entered city government. The political agenda focused on low-rise, medium-density housing, on social housing, and on mixing people with different incomes. This was a sharp contrast to the old approach of ghettoizing the poor in public housing projects such as Regent Park.

Planning initiatives in the seventies greatly affected the quality of life in the City of Toronto. For example, the city bought blocks of houses, tore them down, and created public parks. It forbid residents to transform gardens in front of their houses into parking lots, and rigorously controlled parking in the neighborhoods. Like most of the residents who do not have a garage, I need a parking permit which costs $70 per year. Guests can not leave cars on the street after midnight unless they have a $10 parking permit. In addition, parking permits are limited according to the household’s size.

In the seventies, professionals also started moving back into downtown areas and renovated the often run-down working-class houses. This change clearly distinguished Toronto from most large American cities where renovation of older houses in the downtown areas was less common. The

redevelopment of working-class neighborhoods also prevented the formation of ghettos. Today the City of Toronto has new regulations in place which allow the conversion of industrial buildings (factories and warehouse) into condos. This allows an increase in density, provides affordable housing to first time home buyers, and reduces the flow of people to the suburbs and the pressure for development there.

Suburban Sprawl

While the citizens of the City of Toronto were fighting urban renewal schemes, the metropolitan area was growing continuously on the outskirts. North York, York, Etobicoke and Scarborough were transformed from farmland into suburbs. In 1954, Metro Toronto — a regional government serving these four suburban cities and the City of Toronto — was created as a way to speed ahead suburban development and better control transportation and servicing costs.

However, with urban sprawl getting out of control at the beginning of the seventies, the new Metro Toronto Centered Region Plan called for compact growth, the retention of identifiable communities, and a greenbelt around the metro region to ensure that suburbia did not spread any further.

Pressure by developers who owned vast tracts of land, intensified by pro-growth municipal councils, prompted the government to move away from this plan within a year. Ever since then developers have been free to built where they want to, although some natural areas such as ravines and streams have been protected since the late fifties for flood control reasons. As a consequence the urban area continued to sprawl and one boundary after another set as a limit has fallen. Every farm within one hours’ drive of the City of Toronto was marked for a suburban division. With growth came an improved highway system which facilitated commuting to the workplace in downtown Toronto.

Public transportation in the City of Toronto goes back as far as 1891, with subway lines opening in 1954 and 1966. The city steadily improved its service and today has one of the best transit systems in North America. However, these lines are limited to within Metro boundaries.

The Megacity — Amalgamation a Threat to Neighborhoods?

In the 1990s the large, geopolitical structure of Metro Toronto, with too many layers of government, expensive duplication of services, and financial competition among the municipal governments, led to calls for change. In 1997, the Tory (conservative) provincial government approved Bill 103 to amalgamate the City of Toronto with the five other cities of Metropolitan Toronto. A “Megacity” with 2.3 million inhabitants will be formed on January 1, 1998 with a single city council and mayor. This Megacity will have been formed with little consideration of citizens’ perspectives and without regard to the overwhelming “no-Megacity” vote during a referendum in spring 1997.

Opponents of the Megacity, in particular the citizens of the City of Toronto, fear that the political structure of the new city will be too big for daily decisions regarding individual projects, parks, and community facilities. As the city becomes larger yet has fewer councilors, citizens fear that the Megacity will become an inflexible bureaucracy and that the ability of decision-makers to understand individual neighborhoods may get lost. There is also worry among the citizens that the values of the suburbs will dominate and become a threat to the local characteristics of downtown Toronto.

Toronto vs. San Diego

The ethnic diversity, safe streets, green spaces, people-oriented public places, neighborhood interaction, and good public transportation that characterize Toronto are quite different from what I experienced previously living in San Diego, where suburban sprawl is alive and well.

I lived near that city’s Carmel Valley, known for its beautiful sandstone formations. In the early 1990s new subdivisions and a freeway were built there almost overnight. Destruction of the natural landscape was so complete that there was not much left to remind me of the Valley. I actually got lost driving through a new subdivision. Every house looked alike.

But the most frightening thing was that I never actually saw anybody except an occasional lonely runner while checking out those places. There was nobody sitting in the newly-created parks. The whole place seemed like a ghost town with the exception of the big malls. The subdivision was built without the least regard for social interaction, designed instead for the individual family and the anonymous car driver.

Despite its problems, metropolitan Toronto offers some alternatives to San Diego-style sprawl. Some new subdivisions around Toronto are being planned according to the new urbanist model, aiming at more compact, village-style development. But more importantly, as the recent New Urbanist conference recognized, the City of Toronto’s extensive and well-preserved downtown neighborhoods represent a good alternative model of livable urban communities.

Monika Jaeggi, Ph.D., is a visiting scholar in the Department of Geography at York University.