by Michael Rios

The public spaces of Barrio Logan, a low-income Latino neighborhood in San Diego, proclaim a unique Mexican and Chicano culture. The neighborhood faces the San Diego Bay towards Coronado Island and is thirteen miles from the Tijuana border. Physically it consists of small lots connected by a network of streets and alleys, with a mix of residential, commercial, light industrial and maritime uses. The neighborhood also has a trolley station providing connections to downtown to the north and San Ysidro to the south, bordering Tijuana.

Barrio Logan, originally part of Logan Heights, has been the historic area in San Diego for Latinos of Mexican descent. Many of its inhabitants originally came from Baja California and prior to the 1920s were living and working on both sides of the border. Migration and linkages to Mexico were an important part of Barrio Logan, with trains providing the main means of transportation. The creation of a border check point at Tijuana in 1924 — an attempt to stop migration — and the depression that quickly followed weakened the physical ties between this community and Mexico.

Barrio Logan’s population continued on a downward trend until World War II, when a shortage of labor in the United States created a demand for labor in the shipbuilding industries which lined the San Diego Bay. The growth of such industries led to the rezoning of much waterfront land from residential to industrial use. However, by the 1950s job opportunities were again shrinking and the area was considered a slum by many because of its deteriorating housing stock and an abundance of “yonkes” or junkyards. Cut off from the bay, surrounded by industrial development, and red-lined by financial institutions, the community deteriorated.

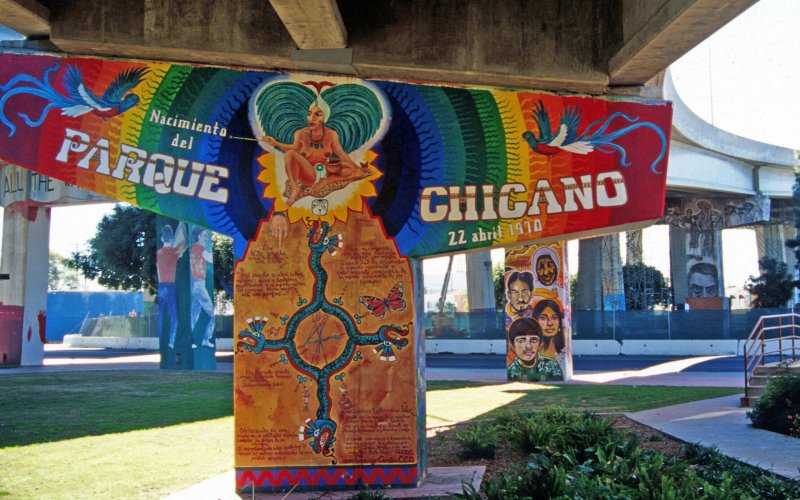

The neighborhood was further assaulted when in 1969 Caltrans began construction of the Coronado Bay Bridge, connecting Coronado Island with a major highway in San Diego. The bridge sliced through the heart of the community and construction required that 1,500 people be displaced from the neighborhood. As a concession, the city promised a 1.6-acre park at the base of the bridge, although the community had already been seeking a place for a larger park. To make matters worse, the State of California announced plans to build a highway patrol station on the same land where the city had promised to build a park.

The community mobilized itself and occupied the construction site for 12 days. An agreement between residents and the city was eventually reached when the city agreed to acquire the site from the state and develop it as a community park. In April of 1973, a handful of artists and 500 painters converged on the park and painted four colorful murals on the bridges’ pillars as a way of marking the event and celebrating Chicano identity. The artists envisioned the park continuing until it reached San Diego Bay. Murals are sequentially painted in the direction of the water.

Today, Chicano Park is the symbolic heart of the community. The creation of this park marked the beginning of community efforts to address other neighborhood problems. A second neighborhood park has also been created near San Diego Bay. In 1991, Barrio Logan was declared a redevelopment area in order to correct ill-conceived past planning decisions. The redevelopment plan attempts to concentrate industrial uses away from residential property as a way of protecting the community. The city also created a “Mercado Commercial Center” in the center of Barrio Logan with new commercial development to be linked to the trolley station, and has carried out streetscape improvements.

Recently a community-based development corporation, the Metropolitan Area Advisory Committee (MAAC) headed by Richard Juarez, has developed 144 units of affordable housing in the neighborhood center. This project received an Urban Land Institute project of the year award in December 1997. The group is also planning a “supermarket” in the Mercado center bringing together a collection of small Latino merchants rather than large chain stores. However, for that reason financing has been difficult to secure. The Mercado will eventually include a cultural art museum linked to Chicano Park celebrating the history of Mexican and Chicano culture and local social movements in the 1960s and 70s.

UE board member Michael Rios is a project manager for the Spanish Speaking Unity Council in Oakland.