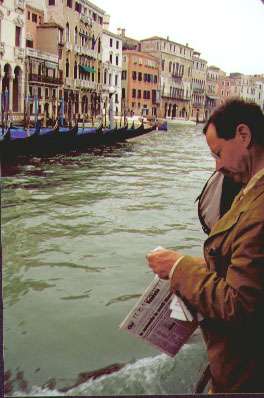

Venice is one of the world’s urban treasures and one of its most unique cities. Built on little more than a large sand bar in the middle of a coastal lagoon, the city’s centuries-old stone palaces, churches, residences, and shops rest on wooden piles driven into the soft sand. Pedestrians jam the carless cobbled alleys, streets, and squares, lingering on the hundreds of footbridges that cross numerous canals and knit the city together. Boats of all descriptions ferry passengers, carry goods, and substitute for fire engines and police cars on the canals traversing the city.

As with other ancient Italian cities, it’s difficult to imagine Venice facing too many problems. Yet a declining population, flood of tourists, water pollution and congestion, and the constant threat of very real floods plague the insular port city, and the fractured nature of local authority makes it difficult to address the problems.

Perhaps Venice’s best-known problem is the appearance that it’s sinking. In fact, the British magazine Geographical reports, it is the lagoon bed itself that has sunk by 9 inches over the past century. This was caused by mainland industries pumping freshwater from the water table beneath the lagoon. This practice stopped in 1970, apparently allowing the lagoon bed to rise slightly. The threat of serious flooding hasn’t abated, however, as global warming seems to have caused rising sea levels near and within the lagoon.

Much as residents of traffic-choked metropolises have learned to deal with congested commutes, Venetians cope with high waters. In the center of many of Venice’s streets, planks are stacked atop structures that look like sturdy metal tables. When tidal surges send water over the streets, city workers lay the planks out as elevated walkways, allowing pedestrian traffic to continue to move, albeit at a slower pace.

More troubling to many Venetians are the city’s declining population and its transformation into a Disney-like tourist center. In 1950, the population of Venice and nearby islands reached 184,000. Today, that population has fallen to roughly 100,000 as birth rates have fallen and Venetians have moved to low-rise apartments and houses in mainland suburbs.

These days, many of the people — frequently a majority — walking the streets of Venice are tourists, speaking a babel of languages, spending Euros in restaurants, hotels, and gift shops. Venice is a city that has long attracted people from near and distant lands, but today’s migrants are different: They stay briefly and they don’t support the type of commerce found in lived-in communities. As a result of declining population and the changes brought about by tourism, Venetians fret about the fate of their culture and future of their city.

Compounding concerns are troubling trends on the waterways: pollution from heavy industries on the nearby mainland and shipping, congestion from unregulated boat traffic, and damage caused to waterside apartments and other buildings by wakes slapping against old foundations.

To begin to address the decay of Venice’s housing stock, analysts say, a balance needs to be achieved between the desire — and nationally mandated requirement — to protect tenants from unaffordable rent increases and the need to finance repairs to old, dilapidated residential structures.

More broadly, addressing some of the environmental issues and concerns about flooding would combine to make the city more livable. Many Venetians — some polls say a majority — support the construction of movable barriers across the openings to the lagoon, but locally powerful Greens oppose the barriers, arguing that cleaning up pollution of the lagoon, closing down waterside heavy industry on the mainland, and excluding large vessels should come first.

HistoryBanter.com – history, humor, pop culture.

BonusPromoCode.com – online promo codes.