Contents

by Tim Alley

Brazil is a country of many big cities, and most of them have their share of urban problems — poverty, overcrowding, sanitation. The city of Curitiba is an exception. In fact, Curitiba is known as “The Ecological Capital of Brazil.” I went there with a video camera to film what an ecological city looks like.

The first place I visited in this city of 1.6 million people was the Curitiba Research and Urban Planning Institute, or IPPUC. There, architects, landscape architects, engineers, transportation planners and administrators work together to coordinate the planning of the city. The institute began in December, 1965 as a recommendation of the Master Plan developed that same year, and now includes more than 200 people.

1965 Plan Establishes Priorities

The 1965 Master Plan set out to enhance the quality of urban life and established priorities — like directing growth, increasing parkland and improving public transportation — that continue to guide the development of the city today.

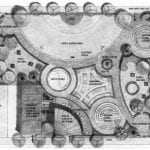

The city controls its growth by setting boundaries. These are large, linear parks which separate Curitiba from its neighbors. In addition to this greenbelt of parks, the 1965 Master Plan defined linear corridors of development called Structural Axes radiating from the downtown. Along these axes are high-rise apartment buildings served by the main lines of the bus system. The radiating axes converge in the city center.

The way downtown Curitiba was preserved as a place for people is now a local legend. A plan called for an automobile overpass through the center of the city which would have destroyed the downtown. Instead in 1972 Major Jaime Lerner sent a team of construction workers to build a street only for pedestrians. Shop owners didn’t want cars removed from the street, and went to court to have this project blocked. Before hearing the judge’s decision, the mayor decided to start construction. On a Friday night the machines started and completed two blocks in two days. When shops opened on Monday morning, everything was done. On Tuesday the judge ruled that the plan was not allowed — but it was too late.

Motorists were furious, and organized a parade of cars to reclaim the street. But when they arrived, city workers blocked them by unrolling long sheets of paper and inviting children to paint in the street. Now, every Saturday morning, this event is repeated in what is now a downtown devoted to people, not cars. Ever since the owners of shops in other areas of the city ask, “when are you going to develop a pedestrian street in my neighborhood?”

Flexible, Efficient Transportation

A big part of what makes Curitiba an ecological city are its buses. In 1974, when the population of Curitiba was about 600,000, one bus line served the entire city. In the 70s and 80s, as the population tripled, the bus network was continually expanded to meet growing demand. Today, the entire system is integrated to allow passengers to transfer between lines easily, quickly and inexpensively.

The transportation system works because it is a hierarchical network in which different buses play different roles. Silver buses have their doors on the left side and only stop at every third stop. They drive with regular traffic on normal streets. Express buses are bright red and have doors on the right side. Many express buses are biarticulated, meaning they are three times as long as normal buses and can carry up to 270 passengers at a time. They operate on special lanes for buses only, such as the center lanes of the structural axes. Orange, yellow and green buses are feeder lines that filter through the neighborhoods, picking people up near their homes and taking them to connect to red or silver buses going downtown. With a single bus fare of about 55 cents, a passenger can get to any destination in the city.

In 1991, Curitiba introduced a simple but brilliant innovation — tube stations. These are elevated glass bus stops where passengers pay their fare, enter through a turnstile, then board at bus level. With the reduced loading and unloading time, buses can carry three times as many passengers each hour as before.

Today, two-thirds of the citizens of Curitiba use buses every day. Researchers estimate this saves 27 million automobile trips each year. Curitiba’s “surface metro” cost 1/300th the price of an underground metro.

A Focus on Social Programs

The current mayor of Curitiba, Raphael Greca, has focused on strengthening social programs, and has helped initiate hundreds of projects ranging from a new system of libraries to assistance for homeless people. One program that teaches people skills so they can contribute to the city is the LICEU program, which offers courses like cooking, sewing, hairdressing, computer programming, and car mechanics. Students are often recent emigrants from the countryside who need job training. The city buys houses in growing neighborhoods and converts them into these schools. People can walk to their classes and because the LICEUs are in their community, students feel comfortable about learning. The three-month courses cost about $4.

In the poorest neighborhoods, the city started a program called the LINE TO WORK. It’s the same as the LICEU program, but classes are taught in recycled buses. A bus is driven to a neighborhood, parked for three months, and set up as a classroom. One bus can hold many classes a day. In the four years these programs have existed, they have trained more than 100,000 people to be part of the job force of Curitiba.

The city also takes the lead in creating jobs. One program called TUDO LIMPO (“All Clean”) hires people who may otherwise be unemployed to do maintenance in their own neighborhoods. They not only get paid, but start to take pride in where they live by helping keep it clean.

But sometimes education and jobs are not enough to help people. So for the most needy segment of the population, the city runs the Fazenda — a farm where recovering alcoholics and drug addicts can get their lives back together and reintegrate into society.

These simple, effective and inexpensive social programs are a fundamental part of the planning that has made Curitiba an environment for people. One of the innovative ways the programs are funded is through a city-owned chain of souvenir shops called LEVE CURITIBA (“Take Curitiba”). The items sold have to do with the city, such as toys made of recycled material, and all profits are reinvested to support social programs.

In addition to developing social programs Mayor Greca has helped design a series of textbooks to teach children about their city, and has been involved in other innovative programs in the elementary schools. For example, the book Licoes Curitibanos, inspired by the Mayor, utilizes lessons from the entire city of Curitiba as a way of teaching citizenship.

As Curitiba grows faster than any other place in Brazil, creative solutions have allowed it to deal with one of its greatest pressures — the demand for housing. Brazil has a problem with favelas — squatter settlements that form when a city is unprepared for quick growth. To avoid this, Curitiba planners prepared a large area on the edge of the city. They installed infrastructure, built streets, and divided lots to be sold. Sixty percent of the new emigrants work in the construction industry, so they already know how to build their own homes. With the purchase of a lot, buyers also receive two trees and an hour with an architect, who can help them organize their new house. And if they are still looking for ideas, the city has created a “technology street” where each house demonstrates an alternative type of building technology.

Teaching Citizens About the Environment

For a city to be truly ecological, it must teach its citizens to be environmentally responsible. Curitiba’s Free University for the Environment is a school where ecological issues are taught to the public. Built in an old stone quarry, it is made of recycled telephone poles. The building rises from the earth and is connected to the landscape.

The city’s “Garbage is Not Garbage” program won a prize from the U.N., and helped people see the environment in a new way. Partly as a result, 90 percent of residents recycle their waste today.

Everywhere you look in Curitiba there is information about the city. Making the city understandable is an important part of making it ecological. For example, there is a line in the cobblestone that runs through downtown. You can walk this line and pass historic buildings, murals, and signs explaining the colorful architecture.There are also information signs at many of the tourist attractions in the city, describing all the programs that make Curitiba an environment for people. Television commercials explain the bus system, and newspapers feature stories about new city projects.

Curitiba has one other important feature — the people of Curitiba. They are interested in their city and committed to making it work. One person who has led the movement to make Curitiba “The Ecological Capital of Brazil” is Jaime Lerner. In 1970 he became mayor and brought his ideas from architecture school to his new office. He also brought the courage to change his city. Over the next 25 years, Lerner and his team transformed Curitiba. His determination has paid off not only ecologically, but also politically. He is now governor of the Brazilian state of Parana, and enjoys one of the highest approval ratings of any politician in Latin America.

I went to Curitiba to see what an ecological city looks like. What I found was that it looks like many other cities. Curitiba’s success proves that with creative solutions which emphasize people and the environment, we can make any ordinary city extraordinary.